Paging technique and Memory Management Unit¶

Processors equipped with MMU are typically used in servers, personal computers and mobile devices such as tablets and smartphones. In this architecture, the linear addresses used by executed program are translated to physical memory addresses using MMU associated with the processor core. This translation is performed with a defined granulation and the piece of the linear address space used for translation to physical address is called a memory page. Typically, the page size used in modern systems varies from 4 KB to gigabytes, but in the past, e.g. on the PDP-10, VAX-11 architectures, it was much smaller (512 or 1 KB).

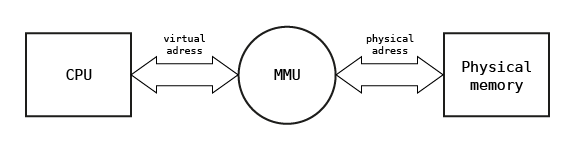

MMU holds set of associations between linear and physical addresses defined for the process currently executed on the core. When process context is switched associations specific for the process are flushed from MMU and changed with associations defined for the new process chosen for execution. The structure used for defining this association is commonly and incorrectly called page table and stored in physical memory. On many architectures associations used for defining the linear address space are automatically downloaded to MMU when linear address is reached for the first time and association is not present in MMU. This task is performed by a part of MMU called Hardware Page Walker. On some architectures with simple MMU (e.g. eSI-RISC) the operating system defines associations by controlling MMU directly using its registers. In this case page table structure depends on software. The role of the MMU in memory address translation is illustrated in the figure below.

In further consideration, the linear address space defined using paging technique will be named synonymously as the virtual address space.

Initial concept of paging technique¶

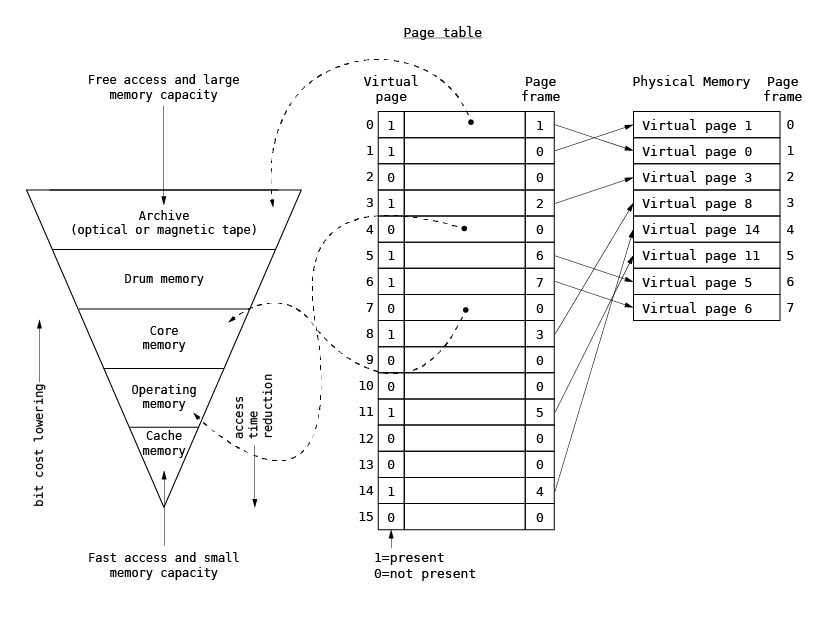

The concept of paging was first introduced in the late 1960s in order to organize the program memory overlaying for hierarchical memory systems consisting of transistor-based memory, core memory, magnetic disks and tapes. Historically, the virtual address space size was comparable to the physical memory size. The page table was used to point to the data location in the hierarchical memory system and to associate the physical memory location, called a page frame, with the virtual page. When the program accessed the virtual page, processor checked whether the page was present in the physical memory via the presence bit in the page table. If the page was not present in the physical memory, the program execution was interrupted and the page was loaded by the operating system into the physical memory via additional bits defining the data location in the page table. Once the presence bit was successfully loaded and set, the program execution was resumed. The original paging technique is presented below.

Current use of paging technique¶

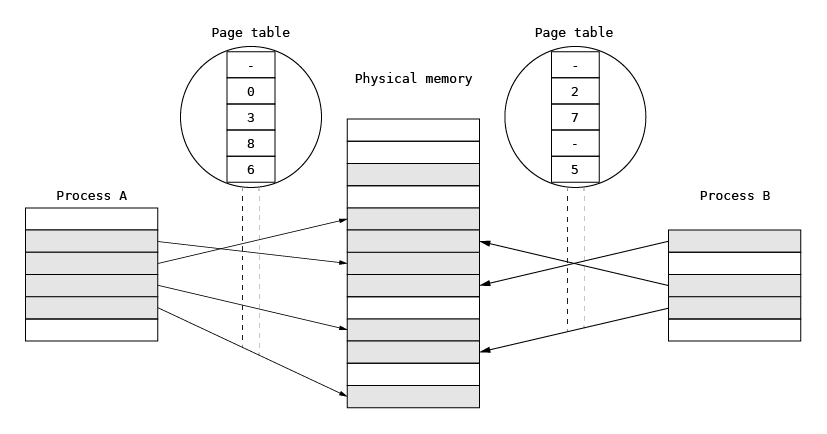

Over the years, paging has morphed into a technique used for defining the process memory space and for process separation. In general-purpose operating systems, paging is fundamental for memory management. Each process runs in its own virtual memory space and uses all address ranges for its needs. The address space is defined by a set of virtual-to-physical address associations for the MMU defined in the physical memory and stored in a structure that is much more complicated than a page table used in early computers. This is necessary in order to optimize memory consumption and speed up the virtual-to-physical memory translations. When a process is executed on a selected processor, the address space is switched to its virtual space, which prevents it from interfering with other processes. The address space is switched by providing the MMU with new sets of virtual-to-physical associations. In this scheme, some physical pages (for example parts of the program text) can be shared among processes by mapping them simultaneously into two or more processes to minimize the overall memory usage.

A memory management system that relies on paging describes the whole physical memory using physical pages.

Page allocator¶

The page allocator constitutes the basic layer of the memory management subsystem in MMU architectures. It is

responsible for allocating the physical memory pages (page frames). In non-MMU architectures, the page allocator

allocates only fake page_t structures used by upper layers and plays a marginal role in memory management. This

section focuses on the role of a page allocator in MMU architectures.

Page array¶

The available physical memory is treated as a set of physical pages (page frames). Each physical page available is

described using the page_t structure. The structure is defined in the HAL, but upper layers assume that some

attributes are defined. The minimum set of attributes is as follows.

typedef struct _page_t {

addr_t addr;

u8 idx;

u8 flags;

struct _page_t *next;

struct _page_t *prev;

} page_t;

The addr attribute stores the physical page address, the flags describe page attributes (see further sections). The

next and prev pointers and idx are used in the page allocation algorithm to construct lists of free pages.

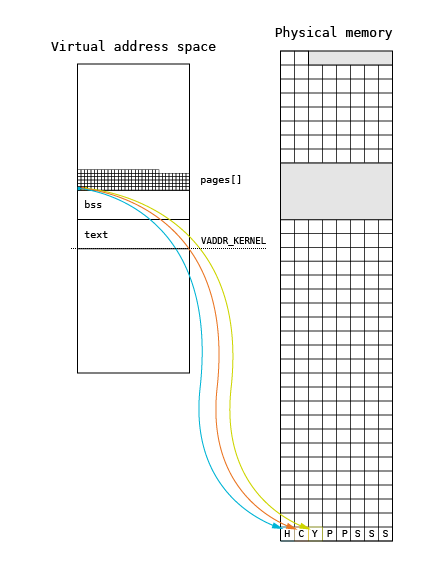

When the memory management subsystem is initialized, the _page_init() function creates an array of page_t structures

(pages[]) using the pmap_getPage() call from the HAL subsystem. This call is used to discover the page frames by

upper (hardware-independent) layers of the memory management subsystem. The page array is located at the beginning of

the kernel heap, right after the kernel BSS segment.

The memory for the structure is allocated using a heap extension. This extension is performed by using the

_page_sbrk() function, which allocates a new page from the pool using the _page_alloc()function and maps it into the

kernel address space directly with pmap_enter() at the top of the heap. Pages are allocated using a regular allocation

algorithm, but data structures used for allocation are not fully initialized. The array creation algorithm is presented

below.

for (page = (page_t *)*bss;;) {

if ((void *)page + sizeof(page_t) >= (*top))

_page_sbrk(pmap, bss, top);

if ((err = pmap_getPage(page, &addr)) == -ENOMEM)

break;

if (err == EOK) {

if (page->flags & PAGE_FREE) {

page->idx = hal_cpuGetFirstBit(SIZE_PAGE);

_page_add(&pages.sizes[page->idx], page);

pages.freesz += SIZE_PAGE;

}

else {

pages.allocsz += SIZE_PAGE;

if (((page->flags >> 1) & 7) == PAGE_OWNER_BOOT)

pages.bootsz += SIZE_PAGE;

}

page = page + 1;

}

/* Wrap over 0 */

if (addr < SIZE_PAGE)

break;

}

The initialization loop in each iteration discovers a new physical page using the pmap_getPage(). The function fills

the newly allocated page_t structure and returns the next valid physical address in the addr argument. The returned

page is flagged as either free or allocated using the flags attribute. The next two upper bits of this attribute

define the page ownership: a page can belong to the kernel, application or bootloader (memory reserved by BIOS on a PC

is marked in this way). The next upper bits define the page usage in the specific domain defined by ownership. For

example, pages marked as allocated by the kernel may be allocated for specific purposes (stack, heap, interrupt table,

page table etc.).

Presentation of page array during the boot process¶

During the kernel boot process, the page[] is presented on the screen using letters and periods. The letter

interpretation will be presented using a sample map for a PC with 128 MB of RAM.

vm: HCYPPSSS[24H][22K][103H]..B[80x][16B][32509.]BBB[101574x][64B]

In this map, the first physical page is allocated to the kernel heap. The second page is used for CPU purposes

(interrupt and exception table). The Y-marked page stores the syspage_t structure used for communication between

the loader and the starting kernel. After this page, there are two pages used for storing structures used for paging

(page directory and page table marked with P). The next pages are allocated for the initial kernel stack. They will

be released after starting the init process, switching into its main thread stack. The next characters

(in square parentheses) contain the information that next 24 pages are allocated to the kernel heap. The next

22 pages store the kernel code and data. These are followed by 103 pages allocated to the kernel heap and two

free pages (marked with periods). The B character informs that next pages are used by the bootloader (BIOS).

This page is followed by a gap (i.e. the gap after the 640 KB of address space). After the gap, there are 16

pages allocated to BIOS and 32509 free pages. At the end of the address space, there are 64 pages reserved by BIOS.

Letter |

Page Type |

Description |

|---|---|---|

. |

|

Free page |

x |

|

Memory gap |

B |

|

Reserved by Bootloader / BIOS |

A |

|

Used by application |

K |

|

Used by kernel for unspecified reasons |

Y |

|

Used by |

C |

|

Reserved for CPU specific purposes |

P |

|

Used for paging |

S |

|

Used as kernel stack |

H |

|

Used as kernel heap |

U |

|

Undefined |

Page allocation¶

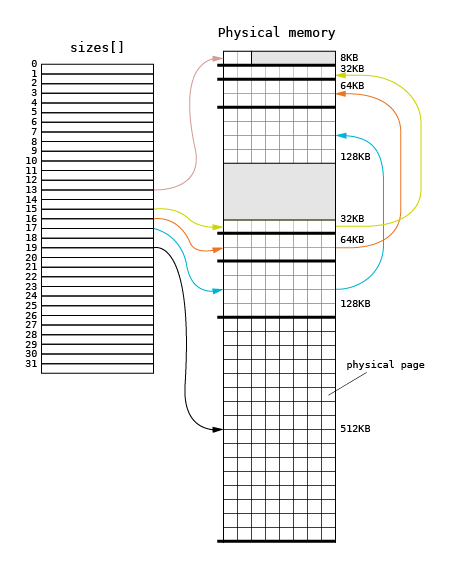

The page allocator in the Phoenix-RTOS kernel is based on a well-known buddy algorithm. The figure below shows a graphical illustration of data structures used in this algorithm.

Each square corresponds to a physical page, with the assumed page size of 4096 bytes. The main structure used in

the allocation is the sizes[] array. The size[] array is created on the basis of the page[] array during

the memory management initialization.

The size[] array contains pointers to lists of physically coherent sets of pages. The n-th entry of sizes[]

array points to the list of sets whose size is the n-th power of 2. For example, an entry with the 0 index points

to page sets whose size is 1 byte. An entry with the 12 index points to sets containing 4096 bytes of physical memory.

The initialization algorithm divides all accessible physical space into regions of maximum size. This means that during

the allocation process a region should be divided into smaller regions and the obtained free regions should be

added to the proper lists pointed by the size[] array.

Sample allocation¶

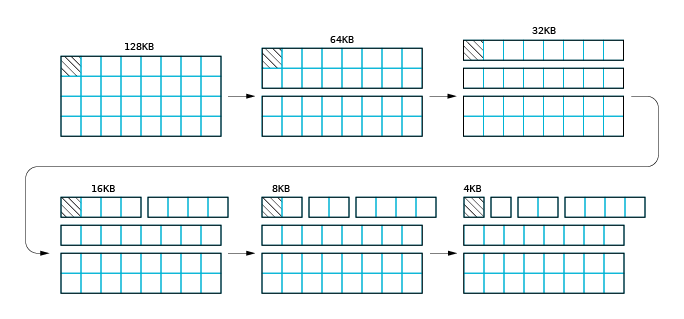

Let us have a look at an allocation process where only one region of 128 KB in size is available, and 4096 bytes

should be allocated. The allocation starts with the lookup of the first region. The starting entry of size[]

array is calculated on the basis of the requested size (4096 bytes). In this case, the starting entry will be 12,

and no list is available in this entry. The lookup is performed for the next entry and finally the 128 KB region

list is found (entry 17). When the first not-empty entry is found, the algorithm proceeds to the next step, which

is illustrated below.

The first page set is removed from the list and divided into two 64 KB regions. The upper 64 KB region is added to the

size[16] entry and then split. The first 64 KB region is split into two 32 KB regions. The upper 32 KB region is

returned to the size[15] entry. Next, the first half of the region is divided into two 16 KB regions, and finally,

only one page is available. This page is returned as an allocation result. The complexity of this allocation is

O(log2N). The maximum number of steps that should be performed is the size of size[] array minus

the log2(page size). The maximum cost of page allocation on a 32-bit address space is 20 steps.

Page deallocation¶

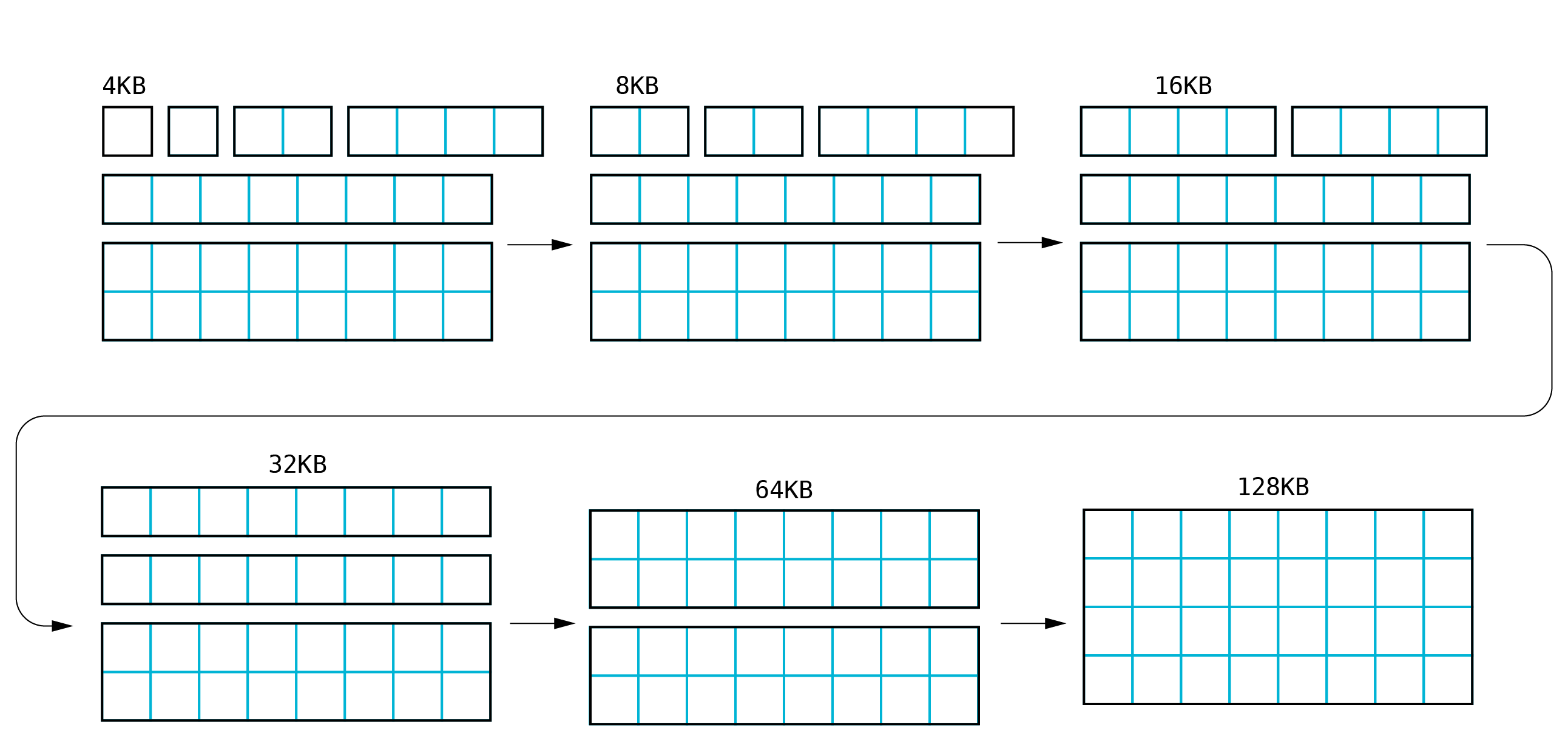

Page deallocation is defined as the process opposite to the page allocation process.

Sample deallocation¶

Let us assume that the page allocated in the previous section must be released. The first step is to analyze the

neighborhood of the page based on the pages[] array. The array is sorted, and it is assumed that the

next page for the released page_t is the page_t structure, describing the physical page located right

after the released page or the page located on higher physical addresses. If the next page_t structure describes

the neighboring page, and if it is marked as free, the merging process is performed. The next page is removed from

the sizes[] array and merged with the page which should be released. If the region created in this way is located

right before the free region of the same size, the merging process is repeated. The next steps are repeated forming

larger regions until there are no free neighboring regions.

Page allocation for non-MMU architectures¶

In non-MMU architectures, the page_t structure is only allocated as needed by upper layers (i.e. a memory mapper).

It does not correspond to a real memory segment. During the kernel initialization, a pool of page_t structures is

created, assuming a given page size. The number of page_t entries is proportional to the size of physical memory.

void _page_init(pmap_t *pmap, void **bss, void **top)

{

page_t *p;

unsigned int i;

pages.freesz = VADDR_MAX - (unsigned int)(*bss);

..

/* Prepare allocation queue */

for (p = pages.freeq, i = 0; i < pages.freeqsz; i++) {

p->next = p + 1;

p = p->next;

}

(pages.freeq + pages.freeqsz - 1)->next = NULL;

..

}

The assumed page size depends on the architecture and the available memory size. For microcontrollers with small memory sizes, the page size is typically 256 bytes.

Page allocation is quite simple. It just retrieves the first page_t entry from the pool. In the deallocation process,

a page_t is returned to the pool. It must be noted that the real memory allocation is performed during the memory

mapping process. All processes and the kernel use the same, common memory map which stores all segments existing in

the physical memory.